NSAIDs

Indications

NSAIDs such as, aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen, can provide significant acute pain relief for mild to moderately painful conditions, including: arthritis, bone fractures or tumors, muscle pains, headache, and pain caused by injury or surgery.

For moderate to severe pain, an NSAID analgesic combined with an opioid analgesic may provide more effective pain relief than either one taken separately. Combining the mechanisms of action of the two drug classes can inhibit both the transduction and the transmission of pain signals.

Whenever pain is severe enough to require an opioid analgesic, adding a nonopioid analgesic should be considered, to leverage an "opioid dose-sparing" effect. Opioid dose sparing refers to the fact that when a nonopioid is combined with an opioid, it may be possible to lower the opioid dose without compromising pain relief.

In a 2022 report by Gazendam, et al., 200 patients undergoing arthroscopic knee and shoulder surgery were randomized to a control group (n= 100) and an opioid-sparing intervention group (n=100). The control group received current standard of care determined by the treating surgeon, which consisted of an opioid analgesic.

The intervention group were instructed to take the prescribed opioid only when the nonopioid protocol was unable to provide adequate pain relief, i.e.:

- 500 mg of naproxen taken orally twice a day as-needed (60, 500-mg tablets) and 40 mg of pantoprazole taken orally daily while consuming naproxen;

- 1000 mg of acetaminophen taken orally every 6 hours as needed (100, 500-mg tablets);

- opioid rescue prescription consisting of 1 mg of hydromorphone taken orally every 4 hours as needed (10, 1-mg tablets)

- patient educational infographic: provided information on both pharmacological and nonpharmacological pain management strategies as well as information regarding the risks of opioid

The trial outcomes:

- The mean amount of oral morphine equivalents (OME) consumed at 6 weeks after surgery in the standard care group was 72.6 mg, compared to 8.4 mg in the opioid-sparing group

- There was no significant difference between the two groups regarding patient pain control satisfaction.

- The most commonly reported adverse effects in the standard care group were drowsiness (20.4%), gastrointestinal upset (17.3%), and dizziness (6.1%), whereas patients in the opioid-sparing group reported gastrointestinal upset (12.6%), drowsiness (7.4%), and dizziness (2.1%).

How NSAIDs Work

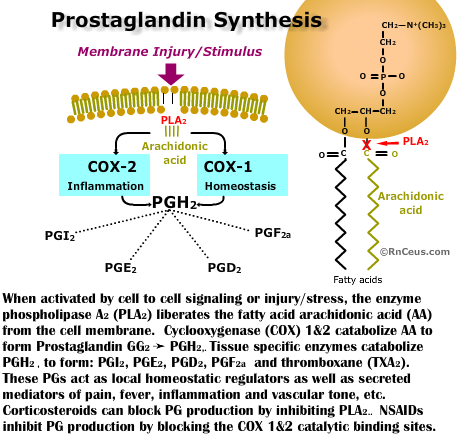

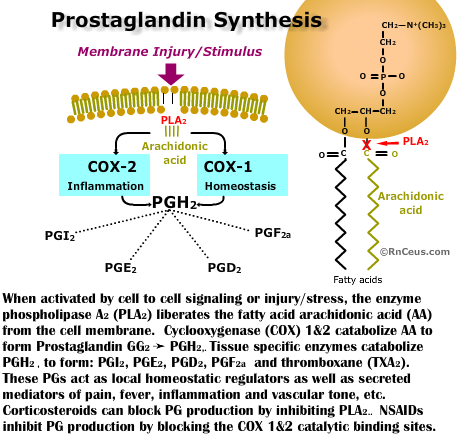

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work by inhibiting the catalytic action of cyclooxygenase (COX), an enzyme that converts arachidonic acid to a prostanoid and thromboxane. Prostanoids are involved in a multitude of physiologic processes including nociception, inflammation and homeostatic processes, while thromboxane is responsible for platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction (Ghlichloo I, 2023).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work by inhibiting the catalytic action of cyclooxygenase (COX), an enzyme that converts arachidonic acid to a prostanoid and thromboxane. Prostanoids are involved in a multitude of physiologic processes including nociception, inflammation and homeostatic processes, while thromboxane is responsible for platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction (Ghlichloo I, 2023).

(Click the graphic to expand and again to minimize)

Prostaglandins

- PGI2 - decreases platelet aggregation, increases renal blood flow, increases vasodilation, inhibits gastric acid production . NSAIDS reduce cyclooxygenase production of PGI2 leading to increased risk of gastric ulcers, and thrombosis, etc.

- PGE2 - increases renal blood flow, mucosal protection, natriuresis, inhibits gastric acid production, pro-inflammatory, propyretic

- PGD2 - increases renal blood flow, inhibits gastric acid production

- PGF2a - decreases progestrone, increases uterine contraction, increases vasoconstriction and bronchconstriction

Thromboxane is responsible for platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction. Thromboxane is produced within platelets when they are exposed to epinephrine, collagen, thrombin, etc.

Types of COX Enzymes

There are three isoforms of COX:

- COX-1 is encoded by the (PGHS-1) gene on human chromosome 9 mainly in the kidneys, gastric, and lung mucosa, as well as on platelets. Cells use COX-1 to convert arachadonic acid to prostaglandin endoperoxide and then to cytoprotective prostanoids involved in, platelet aggregation, vasodilation, renal blood flow, and gastric mucosa protection.

- COX-2 is induced in response to membrane disruption, cellular signaling, inflammation, pain, oncogenesis. COX-2 can be induce in cells of the brain, kidney, and endothelial cells, as well as reproductive tissues, inflamed tissues, and tumor cells.

- COX-3 synthesis of prostaglandin is believed to be restricted to the central nervous system with little or no activity in the peripheral nervous system (Gerriets, V. 2023)

Effects of NSAIDs

Non-selective NSAIDs block the action of both COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes. This can lead to adverse effects, particularly involving the gastrointestinal tract and bleeding risk.

COX-1 produces PGI2 and PGE2 that reduce acid secretion, increase blood flow and stimulate mucus secretion in the esophagus, stomach, and intestine. When this protection is compromised, the patient is at increased risk for potentially life threatening gastrointestinal erosion, perforation and hemorrhage.

COX-2 Selective NSAIDs were developed to block the production of prostanoids that promote pain and inflammation without generating the GI side effects associated with the non-selective NSAIDs.

Common NSAIDs

- Non-selective NSAIDs: ibuprofen, naproxen, ketorolac, indomethacin

- COX-2 selective NSAIDs: celecoxib

- NSAIDs with mixed COX-1/COX-2 inhibition: meloxicam, diclofenac

Adverse Effects of NSAIDs

The most common adverse effects of NSAIDs are gastrointestinal (GI) and cardiovascular (CV).

- GI adverse effects: include heartburn, dyspepsia, ulcers, and bleeding

- CV adverse effects: include increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure.

- The PRECISION-ABPM study demonstrated that celecoxib and naproxen induced either a slight decrease (celecoxib) or a relatively small increase (naproxen) in BP and lower rates of development of hypertension compared with ibuprofen.

- The study projects that BP control in hypertensive osteoarthritis patients could avoid an estimated >70 000 deaths from stroke and 60 000 deaths from coronary heart disease.

- Renal adverse effects: Acute renal failure, chronic renal failure, acute interstitial nephritis, sodium and fluid retention, and hypertension have all been reported as adverse effects of non-selective COX inhibitors.

- Hematologic adverse effects: COX inhibitors have been known to cause platelet inhibition by inhibiting thromboxane A2 production. Aspirin causes irreversible inhibition of COX, and therefore, the duration of platelet inhibition lasts until 7 to 10 days after drug discontinuation.

Preventing and treating NSAID side effects:

NSAIDs should be used with caution in patients with a history of hypertension, GI ulcers, bleeding, or cardiovascular disease. The lowest effective dose should be used for the shortest duration possible.

Some pharmacologic agents have been shown to treat or reduce the adverse effects of NSAIDs:

GI injury (upper & lower)

- COX-2 evidence supporting the benefits of selective COX2 inhibitors over non-selective NSAIDs in the rate of upper GI injury has been demonstrated, but, evidence for prevention of lower GI tract injury in large studies is limited (Guo, C. G., & Leung, W. K. (2020).

- Misoprostol, a prostaglandin analog has been shown, in small studies, to be protective against NSAID small bowel injury. However there was an increased risk of drug-related adverse effects like abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting, diarrhea that caused a high dropout rate (Taha et al. 2018).

- Cox-Inhibiting Nitric Oxide Donors (CINODS) - When experimental CINODS, a new class of anti-inflammatory drugs, were coupled to an NSAID, including: aspirin, flurbiprofen, naproxen, and diclofenac, GI injury was minimized in early animal studies (Wallace, J. L., & Del Soldato, P. 2003)

- Intestinal Microbiota plays a key role in NSAID-induced small intestinal damage. Otani, et al. report that mucosal barrier disruption due to NSAID-induced prostaglandin deficiency, exposes intestinal epithelial cells to gram-negative bacteria and other enteropaths which causes the exposed epithelials to release proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) and interleukin-1βeta (IL-1β). They also suggest the proton pump inhibitors can exacerbate injury by inducing intestinal dysbiosis. Their research suggest that modulating intestinal microbiota with probiotics and rebamipide prevented NSAID-induced small intestinal injury (Otani, et al. 2017).

- Proton Pump Inhibtors (PPIs) raise gastric pH, thereby suppressing NSAID induced small bowel injury. However, long-term use of PPIs can alter small bowel bacterial growth that increase the risk of small bowel and colon injury from enteropaths like C. difficile. In addition patients should be warned against discontinuing PPI use without first consulting a provider because rebound acid production is a potential risk when tapering the dose is not involved.

- Mucoprotective agents

- Rebamipide alleviates NSAID associated GI injury by promoting production of endogenous mucoprotective prostiglandins and it modulates small bowel microbiota.

- Irsogladine has been shown in small studies and animal studies to be protective against NSAID injury from esophagus to small intestine.

Osteoarthritis (OA)

There is currently no therapy to cure or reduce the progression of OA. Ibuprophen and other NSAIDS a frequently prescribed for the pain and inflammation associated OA.

A major study by Luitjens and colleagues, challenged our understanding of NSAIDs in OA, finding no evidence of reduced inflammation after 4 years in 277 patients treated with NSAIDs compared to 793 untreated controls. Infact, NSAID use can worsen inflammation and cartilage condition perhaps due to increased activity.

Patient Teaching

Nurses can help patients achieve the benefits of NSAIDs while reducing adverse effects by ensuring that patients follow these guidelines:

- Don’t take an NSAID with alcohol.

- Don’t take more than one type of NSAID, and only those medications as ordered.

- Take NSAIDs with a full glass of water or milk, with meals, or with a prescribed antacid. Remain upright 30 minutes after administration to reduce gastric irritation or ulcer formation. • Unless contraindicated, drink 2-3 L of water a day.

- Report any changes in stool consistency or symptoms of gastrointestinal irritation, any bleeding episodes, ringing in the ears, skin rashes, sudden weight gain and decreased urine output, fever or increased joint pain.

- Use caution when operating machinery or when driving a car, as NSAIDs may cause dizziness or drowsiness.

- If the individual is a diabetic, he or she should be aware of interactions between specific NSAIDs and hypoglycemic agents.

- Notify all healthcare providers of all medications taken.

- Keep all medications, both prescription and over-the-counter, in a safe place out of the reach of children.

Summary

NSAIDs are effective medications for mild to moderate pain relief and inflammation reduction. However, they can have serious adverse effects, particularly in the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular systems. Careful consideration of the risks and benefits is essential before starting NSAID therapy.

Instant Feedback:

Selective NSAIDs affect the action of the COX-2 enzyme.

References

Gazendam A;Ekhtiari S;Horner NS;Simunovic N;Khan M;de Sa DL;Madden K;Ayeni OR; (2022). Effect of a postoperative multimodal opioid-sparing protocol vs standard opioid prescribing on postoperative opioid consumption after knee or shoulder arthroscopy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36194219/

Gerriets V, Anderson J, Nappe TM. Acetaminophen. [Updated 2023 Jun 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482369/

Ghlichloo I, Gerriets V. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547742/

Guo C. G., & Leung, W. K. (2020). Potential Strategies in the Prevention of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs-Associated Adverse Effects in the Lower Gastrointestinal Tract. Gut and liver, 14(2), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl19201

Luitjens, J., Gassert, F., Joseph, G., Lynch, J., Nevitt, M., Lane, N., ... & Link, T. (2023). Association Of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs On Synovitis And The Progression Of Osteoarthritis: Data From The Osteoarthritis Initiative. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 31, S411-S412

Otani, K., Tanigawa, T., Watanabe, T., Shimada, S., Nadatani, Y., Nagami, Y., Tanaka, F., Kamata, N., Yamagami, H., Shiba, M., Tominaga, K., Fujiwara, Y., & Arakawa, T. (2017). Microbiota Plays a Key Role in Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug-Induced Small Intestinal Damage. Digestion, 95(1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000452356

Pain management best practices - hhs.gov. (2019). https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pmtf-final-report-2019-05-23.pdf

Ruschitzka, F., Borer, J. S., Krum, H., Flammer, A. J., Yeomans, N. D., Libby, P., Lüscher, T. F., Solomon, D. H., Husni, M. E., Graham, D. Y., Davey, D. A., Wisniewski, L. M., Menon, V., Fayyad, R., Beckerman, B., Iorga, D., Lincoff, A. M., & Nissen, S. E. (2017). Differential blood pressure effects of ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib in patients with arthritis: the PRECISION-ABPM (Prospective Randomized Evaluation of Celecoxib Integrated Safety Versus Ibuprofen or Naproxen Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurement) Trial. European heart journal, 38(44), 3282–3292. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx508

Taha, A. S., McCloskey, C., McSkimming, P., & McConnachie, A. (2018). Misoprostol for small bowel ulcers in patients with obscure bleeding taking aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (MASTERS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The lancet. Gastroenterology & hepatology, 3(7), 469–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30119-5

Wallace J. L. (2012). NSAID gastropathy and enteropathy: distinct pathogenesis likely necessitates distinct prevention strategies. British journal of pharmacology, 165(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01509.x

Wallace, J. L., & Del Soldato, P. (2003). The therapeutic potential of NO-NSAIDs. Fundamental & clinical pharmacology, 17(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00125.x

© RnCeus.com

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work by inhibiting the catalytic action of cyclooxygenase (COX), an enzyme that converts arachidonic acid to a prostanoid and thromboxane. Prostanoids are involved in a multitude of physiologic processes including nociception, inflammation and homeostatic processes, while thromboxane is responsible for platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction (Ghlichloo I, 2023).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work by inhibiting the catalytic action of cyclooxygenase (COX), an enzyme that converts arachidonic acid to a prostanoid and thromboxane. Prostanoids are involved in a multitude of physiologic processes including nociception, inflammation and homeostatic processes, while thromboxane is responsible for platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction (Ghlichloo I, 2023).